I’m pretty sure any home excavation in the Hudson Valley will reveal old bricks. We have found about 5 or 6 different bricks each with the makers’ name. They are rather attractive and we will keep them, I will include some photos, but first a bit of history. By the way, most of this is new to me and I find it fascinating, I hope you do too.

At the turn of the 20th century, the Hudson Valley was the brickmaking capital of the world, producing more than a billion bricks a year and employing nearly 10,000 people in more than 120 brickyards. By the late 1970s, the once-mighty molded-brick industry was no more. How and why did this industry become so mighty in the Hudson Valley and why the decline?

I have found what I think to be the major reason for the Hudson Valley brick boom, they are:

-

The raw materials. The raw materials for clay are found in abundance in Hudson Valley. During the last Ice Age in the Hudson Valley area, blankets of ice weighing millions of tons crushed the rocks of many of the mountains into a deposit of flour-textured, rich blue clay. This came to rest in the bays and coves of the newly carved Hudson River. In 1928, test borings made in the Hudson off the old Cofferdam in southern Haverstraw, drilled 100 feet deep and still did not drill through the clay. The Hudson valley clay deposits were known to be the most extensive in America.

-

James Wood’s revolutionary practice. In 1829 James Wood introduced a revolutionary practice into the production of Hudson River bricks. In that year Wood patented the use of crushed coal as a new ingredient in the brick clay mixture. This innovation had the result of reducing the brick firing time as well as fuel consumption by half.

-

Easy access to coal. The Rondout Creek in Kingston is part of the Delaware & Hudson Canal which was the main route for anthracite coal from the Carbondale coalfields in Pennsylvania. As mentioned above coal was an important ingredient to the clay recipe as well fueling the kilns.

-

The great fire of New York city. New York city’s demand for brick skyrocketed after a night watchman noticed smoke coming out of a dry-goods store in the city’s business district on December 16, 1835. Although 56 engines and 1,000 firemen fought the blaze for 16 hours, the Great Fire of 1835 burned more than 52 acres, destroying 674 buildings and driving 14 of the City’s 25 fire insurance companies into insolvency. It was the largest, most costly fire America had ever seen.

Lawmakers unwilling to risk another such tragedy passed a series of building codes requiring fireproofing. Although marble, brownstone, cut stone and brick all played major roles in New York construction after wood dwellings were outlawed, brick was the least expensive. It became the most frequent choice of architects and builders. As the City’s population increased, the demand for brick also rose. Hudson Valley brickmakers rushed to heed the contractors’ calls, and the local brickyards prospered.

And then the decline (from the hudsonvalleyone.com).

New materials, new standards.

The good times for Hudson Valley brickmakers came to an end around the advent of World War I. New construction material such as steel and concrete began to cut into the brick market. The market price of brick hovered slightly higher than the cost of production. To combat the slump, the brickmakers modernized their plants, cutting down on their labour needs. Only technologically progressive plants with new marketing strategies survived. By the end of World War II, only ten brick plants were left in the Hudson Valley.

Attempts by the industry to hold on ultimately failed. By the 1940s, new transportation options meant that New Yorkers could live in the suburbs and still work in the City. The suburban single-family dwellings they built weren’t subject to the City’s stringent fire codes, and brick was no longer required.

The Hudson Valley brick industry lost its transportation edge, too, and designers and architects became more precise when ordering building materials. The high compression standards handed down from the American Society for Testing Materials – unnecessarily high, local brickmakers insisted – were generally beyond the reach of Hudson Valley molded brick. That was the final blow.

Ponckhockie housed a lot or the European migrant workers for the Hutton Brickyard which is half a mile away. If you visit the nearby beaches they are littered with bricks.

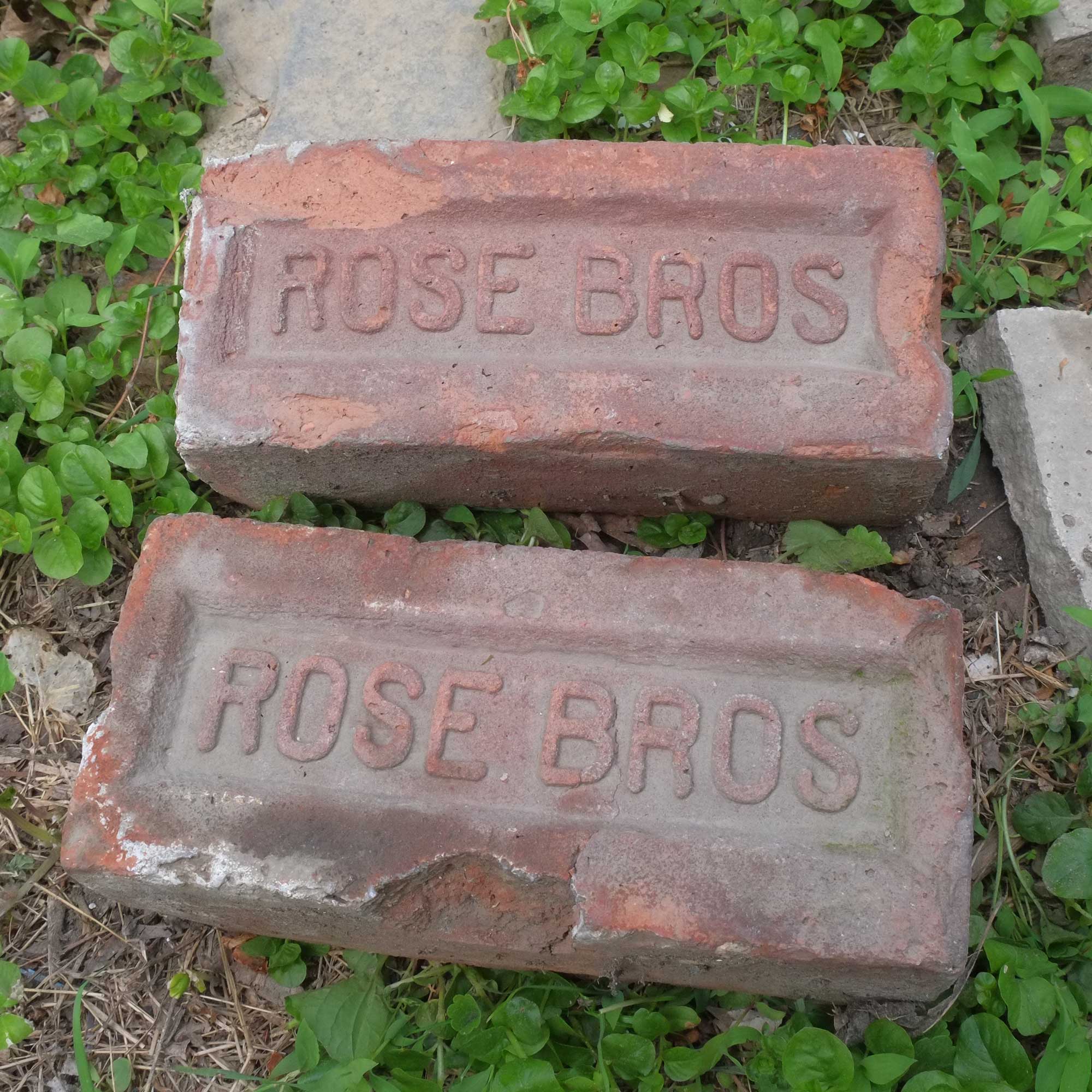

Below are some of the bricks which we dug up in the garden. The history of all these local brickworks can be found at brickcollecting.com. Sorry, I can’t give you links to direct links for each brick, still, it’s a very useful and informative site.

Travelling in and around Kingston there are many relics from both the brick and the cement works. I hope some of these can be preserved, I know I have my eye on a beautiful chimney stack on the Rondout which desperately needs some TLC. So if there is anyone out there with more money than sense, come talk to me.

These facts were cobbled together from these far more informative data sources: